I first visited Stonehenge at some point in the 1960s, when my parents took me and my little sister there for an outing one warm summer’s day. The photographic record of our visit was lost in the house fire of 2018, which I think is a great shame, but other people suffer far, far worse.

However, I have a clear memory of clambering around these vast stones, lost in childish dreams, wondering who built the ruins and what on Earth for? At that time, I was too young to have read any mythology featuring Cyclopean structures, novels by Dennis Wheatley or Thomas Hardy, or anything else containing history or theories about the place.

All the same, I never forgot this enchanted visit and as the decades passed, I read everything I could concerning Stonehenge, as well as visiting the ruins again a few times. In 1996, I moved from London to a village called Netheravon on Salisbury Plain.

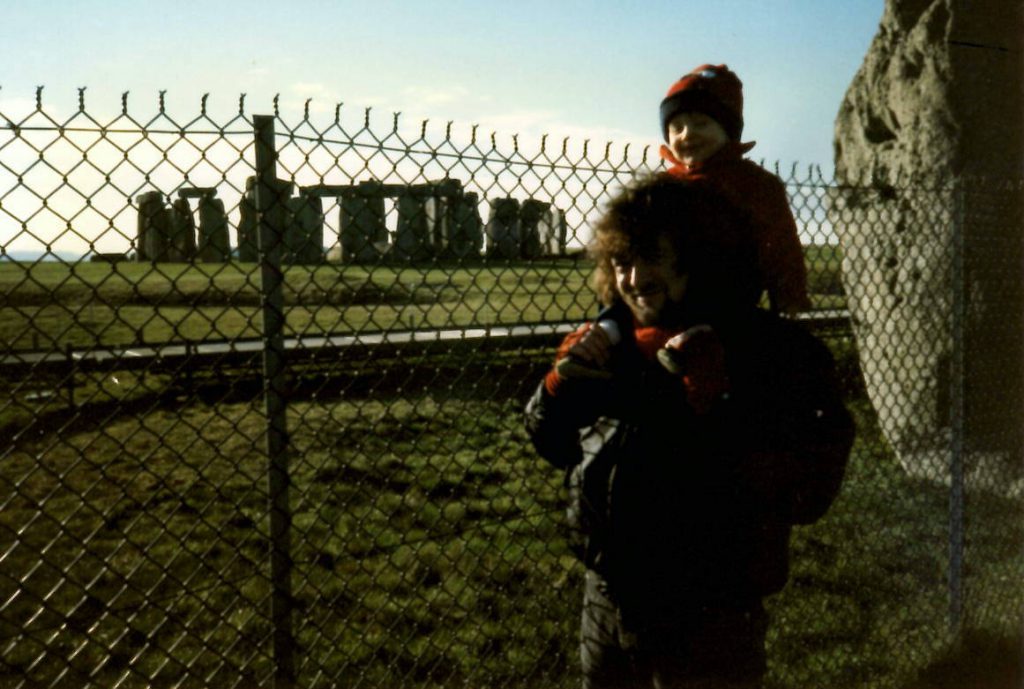

My residency there entitled me to a free local’s pass to the nearby ruins and I ended up visiting the place roughly three times a week for a decade – sometimes alone, sometimes with my young family. My two children absolutely loved the place and they grew up learning to walk there, as well as being delighted by the top quality ice cream and hot chocolate on sale.

In 1998, I made a ten minute film on Stonehenge for ITV West and in the same year, I made an appearance as someone well-versed in the legends attached to Stonehenge during an interview for the BBC’s Style Street. At the same time [I think] I was one of only one hundred people to be invited to Stonehenge to celebrate the Summer Solstice, this being when the crowds were banned from the place and kept away by legions of police.

In January 2000, I started work at Wessex Archaeology and I soaked up everything I could find and learn about nearby Stonehenge. I became aware of more books on the subject and I spoke at length to some of the authors of those books. I continued my regular visits to Stonehenge itself, speaking to as many of the staff as I could about what they knew about the place and what they felt, as well.

I was one of the first people to gaze closely at and examine the remains of the Amesbury Archer after they been excavated in 2002, and to inspect the many grave goods he’d been buried with. As part of the Communications Department, I facilitated visits to the Archer’s remains by curious contingents of the world’s press, who descended on Wessex Archaeology by the score when news of the discovery of the Amesbury Archer was made public. A year later, I filmed the excavation of the Boscombe Bowmen and I also worked on the A303 Stonehenge Test Pit programme.

And so it goes. There were many other details of the time I spent studying Stonehenge or Stonehenge-related subjects prior to leaving Wessex Archaeology in 2003, but there are limits to my powers of recall on these matters, partially because they were all spread out over the course of nearly 4 years.

I used to visit Stonehenge regularly for years before, during and after my time at Wessex Archaeology. I attended just about every one of the open access events while I lived on Salisbury Plain, and I enjoyed some private visits to the ruins that I’d arranged through the good offices of Clews Everard, the lady who was the director of Stonehenge over this period.

Shortly after leaving Wessex Archaeology, I began work on the first incarnation of Eternal Idol. I had become aware of the intense worldwide interest in Stonehenge that was coupled with a profound frustration because the archaeologists had so little to say about the place. My original aim was to write for my own pleasure, because I had a great deal to say about the place and by the time Eternal Idol disappeared offline in 2014 or so, I’d written something in the region of 700 essays on the ruins, as well as some on Silbury Hill.

Over the years, I must have written roughly the same amount in replies to the countless people who visited my site and left a comment there. As a direct result, my written work started to appear in the local, national and international press, and on radio and television. And after the publication of my book The Missing Years of Jesus, this intense interest grew and grew.

I was interviewed by the late Colin Fry for the BBC to discuss the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics, something I was extremely flattered by, but quite possibly the greatest honour arising from Eternal Idol was when I was invited to speak at St James’s Church in London’s Piccadilly in 2010.

One legitimate way of describing my book would be to say that it was an intense study of the first verse of William Blake’s 2005 poem And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time? better known today as the song Jerusalem, Britain’s unofficial national anthem. The great William Blake had been baptised in St James’s Church, so for me to be invited to speak about arguably his most famous verse in this place was a huge honour.

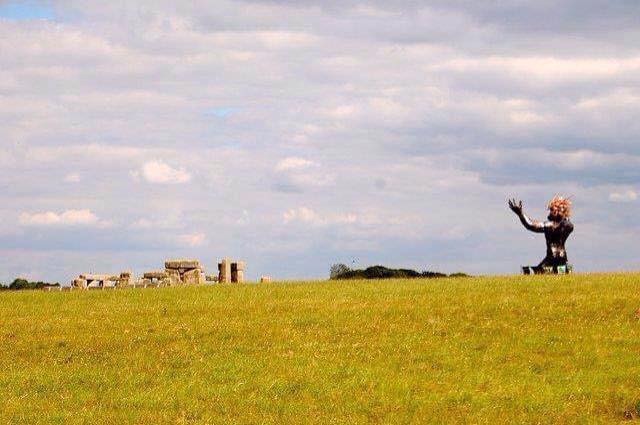

I was the prime mover in getting the giant statue of The Ancestor to Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice in 2010, this being the first artwork that had ever been exhibited at Stonehenge. In 2005, I moved from Salisbury Plain to Devon and it was at this time that popularity in Eternal Idol began to surge.

I would regularly travel back to the area to visit the excavations undertaken by the Stonehenge Riverside Project, something I enjoyed doing, but I was often asked to travel there by production companies who’d become aware of my standing as an expert on the ruins, to give my ‘professional opinion’ to whatever aspect they were making a report or film about.

However, as getting money or payment out of these people was like getting blood out of a stone, I always declined their requests and thought no more of the matter. There are many other aspects of my association with Stonehenge over the decades, the most recent being my visit to the staggering Stonehenge exhibition at the British Museum in 2022, but I hope that the above brief account will be satisfactory for now, regardless of the reason you’re reading this.